How far would you go to make sure learning matters for your students? Would you make a promposal to model Brittany Mason? Create a Vine to send to soul singer Maxwell? Mass tweet Chipotle? Share with your students that you glued your ears to your head when you were twelve and never went to prom?

How about turn down a six-figure salary as Susan Lucci’s love interest to teach high school social studies?

If you’re Nick Ferroni, that was your Friday of last week.

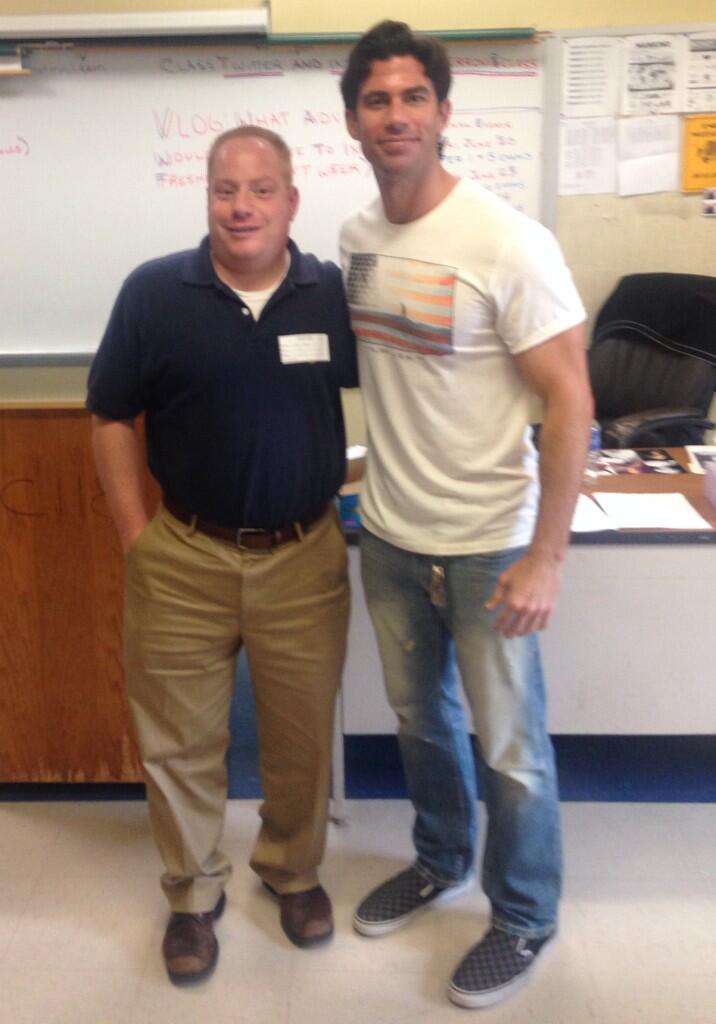

I met Nick through Twitter. Both of us are New Jersey teachers, went to Rutgers, and are around the same age. But, that’s about where it ends on its surface. Nick was a three-star high school athlete, a scholarship division I football player, made some money underwear modeling, and had walk on roles on a soap opera. I wear underwear, played sports, and hated soap operas.

If you look at our picture together, there’s me on the left, and the man who Men’s Health called “One of the 25 fittest men in America” on the right. Nick’s biggest takeaway from this picture? His forehead looks shiny. My biggest takeaway: my body looks like Mr. Potato Head and it’s time for me to get a personal trainer.

Where Nick and I are similar is where we matter: we’ll both go to any lengths to make sure students learn, and how we define learning is much deeper than what’s in any textbook, teacher’s guide, or curriculum. We’re looking at students long-term: what impact will they have on society, and what impact will society have on them? What can we do to aid students so they have a positive experience in life, bouyed with a skill set transferrable to any situation. Can we teach them to solve problems, collaborate, advocate, compromise, and think creatively? Can we get them to push their boundaries from what they think they can do to what we think they can do?

Nick will buy gym memberships and train students who need a positive emotional release. He has a stack of protein bars in his desk in case his students get hungry. He leverages his experiences in theatre and the arts to invite in Maxwell, Brittany Mason, Brian Leonard, and more, to talk about their life experiences. Then, Nick weaves these experiences to draw parallels to the subject he teaches. Because, when he shuts the door, Nick is the curriculum. And, he takes that job seriously.

Which is why, when I have an opportunity to hang with a high energy, humble, creative rockstar educator, I’m going to do it. Even if it means waking up earlier than usual, driving an hour, and going to another school when my district is closed. This is probably how Nick’s students feel when they come to school: that there’s something worth coming inside for. And, that is half the battle.

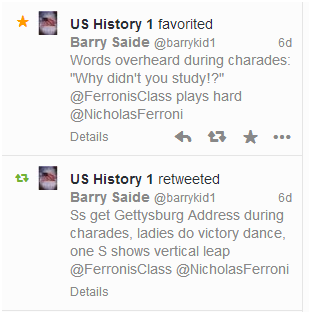

Nick allowed me to live tweet the charades his students did to prepare for the US History 1 exam they had coming up. The energy, enthusiasm, and engagement I saw from the students and their teacher made me want to join in. Here are a few of them, as well as the class Twitter feed:

When I left later that day, I learned two things about Nick and his students: they have a real desire to eat Chipotle before their lives are over, and I want to spend more time with them. I hope both happen soon so we can cross them off our bucket lists. Maybe we can all go to Chipotle together? (FYI, still waiting for a tweet-back from Rusty).